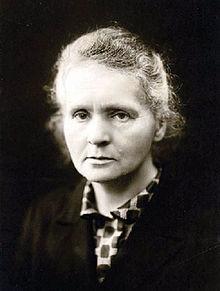

Women’s History Month: Women in Chemistry! Marie Skłodowska Curie, “Madame Curie”

Marie Skłodowska Curie, “Madame Curie,” was a Polish and naturalized-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person, and only woman to win twice, the only person to win a Nobel Prize in two different sciences, and was part of the Curie family legacy of five Nobel Prizes. She was also the first woman to become a professor at the University of Paris, and in 1995 became the first woman to be entombed on her own merits in the Panthéon in Paris.

She studied at Warsaw’s concealed Flying University and began her practical scientific training in Warsaw. In 1891, aged 24, she followed her older sister to study in Paris, where she earned her higher degrees and conducted her subsequent scientific work. She shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with her husband Pierre Curie and with physicist Henri Becquerel. She won the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

During World War I, Marie Curie recognized that wounded soldiers were best served if operated upon as soon as possible. She saw a need for radiological field centers near the front lines to assist battlefield surgeons. Marie obtained X-ray equipment, vehicles, auxiliary generators, and developed mobile radiography units to support them. She became the director of the Red Cross Radiology Service and set up France’s first military radiology center. Assisted at first by an army doctor and by her 17-year-old daughter Irène, Curie directed the installation of 20 mobile radiological vehicles and another 200 radiological units at field hospitals in the first year of the war. Later, she began training other women as aides.

In 1915, Curie produced hollow needles containing “radium emanation,” later identified as radon, to be used for sterilizing infected tissue. It is estimated that over a million wounded soldiers were treated with her X-ray units. In spite of all her humanitarian contributions to the French war effort, Curie never received any formal recognition of it from the French government.

Also, promptly after the war started, she attempted to donate her gold Nobel Prize medals to the war effort, but the French National Bank refused to accept them. She did buy war bonds, using her Nobel Prize money. She said:

“I am going to give up the little gold I possess. I shall add to this the scientific medals, which are quite useless to me. There is something else: by sheer laziness, I had allowed the money for my second Nobel Prize to remain in Stockholm in Swedish crowns. This is the chief part of what we possess. I should like to bring it back here and invest it in war loans. The state needs it. Only, I have no illusions: this money will probably be lost.”

Her achievements included the development of the theory of radioactivity (a term that she coined), techniques for isolating radioactive isotopes, and the discovery of two elements, polonium, and radium. Under her direction, the world’s first studies into the treatment of neoplasms were conducted using radioactive isotopes. She founded the Curie Institutes in Paris and Warsaw, which remain significant centers of medical research today. During World War I, she developed mobile radiography units to provide X-ray services to field hospitals.

Marie Curie died in 1934, aged 66, at a sanatorium in Sancellemoz (Haute-Savoie), France, of aplastic anemia from exposure to radiation in the course of her scientific research and the course of her radiological work at field hospitals during World War I.

Explore Chemistry with your students with these hands-on RAFT ideas:

RAFT proudly recognizes Marie Curie during Women’s History Month! Please check the following link for more information about Women’s History Month: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women%27s_History_Month